The work performance of housing agents is key to enhancing the profitability and sustainable development of the real estate brokerage industry. An outstanding performance by housing agents translates to more sales, increases the agents’ income, and helps them achieve organizational objectives. Thus, this study introduced transformative leadership and proactive personality traits as extrinsic factors and mediator variables into a structural framework on the causal relationships among work engagement, work meaningfulness, and job performance. Structural equation modeling was used to analyze the data collected through online and in-person questionnaires. A total of 860 questionnaires were recovered, of which 548 were valid, indicating an effective response rate of 63.7%. The empirical results revealed that transformative leadership significantly and positively influences job performance through work engagement. In addition, proactive personality traits significantly and positively influence job performance through the work meaningfulness as a mediator. Therefore, this study highlights the importance of transformative leadership and proactive personality traits as forerunners of the work meaningfulness and work engagement that influence job performance.

Byars and Rue [1] identified job performance as a measure of employee productivity. Managers can provide appropriate incentives, rewards, assignments, and promotions based on employees’ job performance. Job performance is thus indispensable to a company’s success. Subordinates with excellent job performance increase their company’s profits and broaden its prospects. Job performance strengthens employees’ self-management and empowers their sense of responsibility so that they understand what they should do to meet expectations. Therefore, job performance has always been an important topic of research.

Most previous studies have expounded the factors related to job performance, such as organizational commitment, knowledge management, reward systems, work engagement, career development, employees’ self-leadership, and job crises [2]- [5]. For example, organizational commitment is one of the most common factors affecting job performance. Employees gain satisfaction from completing tasks, shaping their identification with their organization, enhancing their work motivation, and affecting their job performance.

By adopting appropriate reward systems, company leaders can motivate their subordinates to go beyond their basic job demands and meet the organization’s mission and goals. Therefore, subordinates may become more innovative and committed, affecting their job performance [7]. Employees are satisfied when they complete their assigned tasks and are motivated to set clearer goals and more efficient strategies to achieve them. As a result, they become more adept and dexterous in managing their workflow, enhancing their job performance ([4], [8]. Leaders can apply knowledge management approaches such as education, guidance, and stimuli to increase subordinates’ intrinsic motivation and dedication, which inherently enhance job performance [4], [9], [10]. Furthermore, organizations can use material rewards to instill happiness in employees. Rewarding employees for their excellent behavior or efficiency at work enhances their job performance [11] Career development is also an important determinant of job performance. Employees who possess stronger intrinsic psychological motivators such as satisfaction and identification with their organization and career are more engaged in their work and strive to obtain job promotions, enhancing their job performance [12]. The relationships among the work meaningfulness, work engagement, and job performance have spurred much interest among researchers. Petrou, Demerouti, and Schaufeli [13] and Pak et al. [14] identified work meaningfulness as a component of job performance because it fluctuates with company policy, salary, and benefits. Because of its instability and volatility, work meaningfulness is regarded as a forerunner of job performance. On the other hand, supervisors shape attractive prospects for their employees by motivating them and enhancing their work engagement and role within the organization [15], [16]. Interestingly, transformative leadership and proactive personality traits are also precursors of work meaningfulness and job performance. Transformative leadership can be defined as a leader’s efforts to become a role model to their employees to progress toward positive changes, developments, and work attitudes, triggering employees’ dedication at work [17] and probably enhancing their work engagement and work efforts [18]. Employees with proactive personality traits exhibit high self-regulation, which is shaped by motivational skills and consists of motivation control and emotion control [19]. The positive effects of proactive personality traits on work meaningfulness have been empirically demonstrated in the literature [20]- [22].

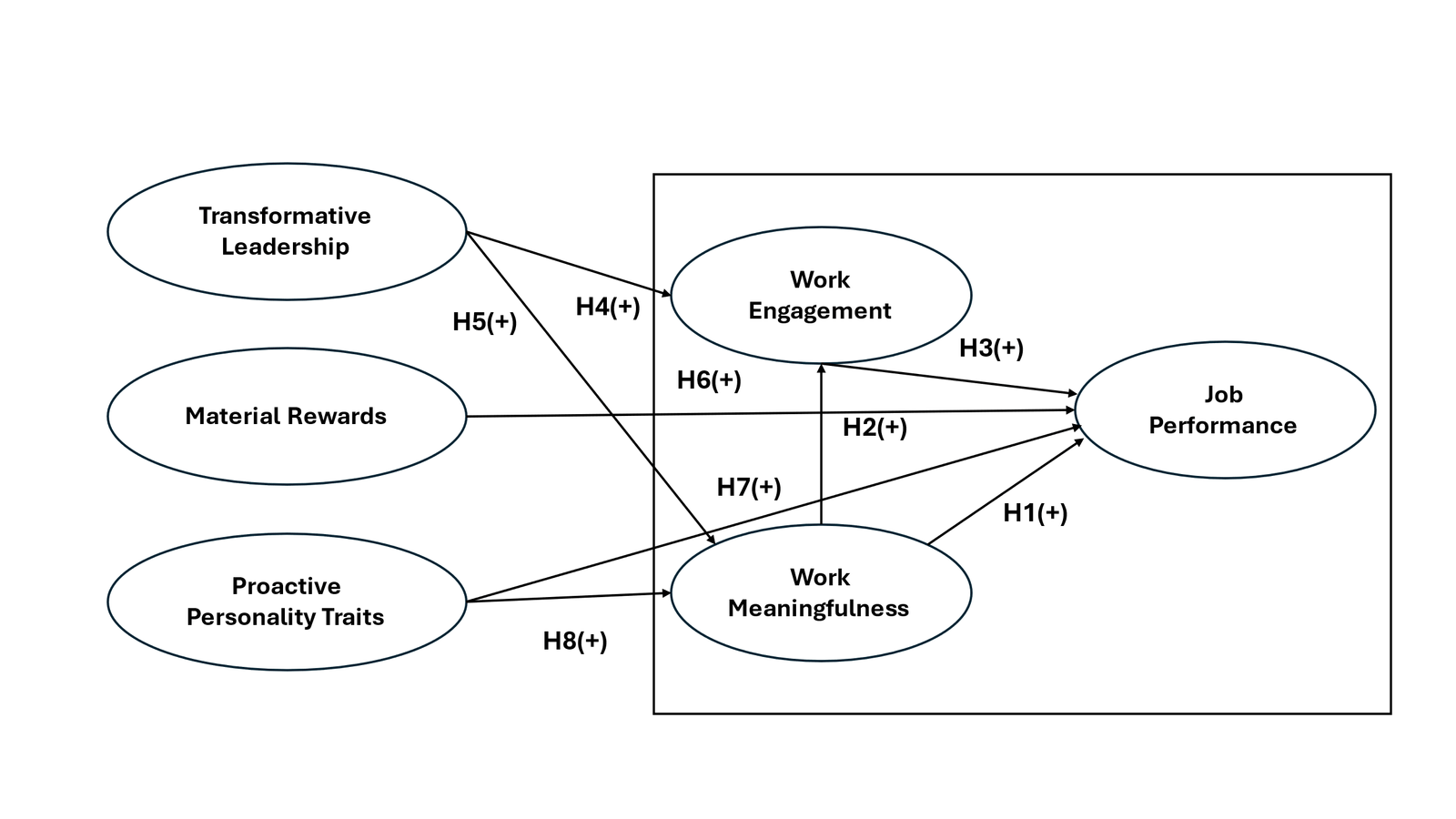

Thus, this study added two extrinsic factors (transformative leadership and proactive personality traits) into an existing framework of the structural and causal relationships among work engagement, work meaningfulness, and job performance. The framework was used to examine the effects of work engagement, work meaningfulness, and the subsequent job performance, and to explore whether proactive personality traits affect job performance through work meaningfulness as a mediator variable.

Work is defined as the objectives that one wishes to achieve through effort. When a person develops feelings toward and understanding of their job, they will recognize the meaning of their job, the role they play, and why they perform work tasks. An employee who is extremely passionate and enthusiastic about their job has high expectations and meaningful objectives for their job, and vice versa. A positive work experience may involve marking specific behaviors as important emotional responses, such as pride, encouragement, satisfaction, enhancement, or personal mastery [23], [24]. Rosso, Dekas and Wrzesniewski [25] suggested four sources of work meaningfulness: the self (personal values, motivations, and beliefs), others (colleagues, leaders, groups, communities, and family), the work context (job task design, organizational mission, and financial environment), and spiritual life (spirituality and sacred calling). Bruef and Nord [26] affirmed that work meaningfulness can be one’s understanding of the work objectives or sense of achievement at work. Meaningful work contributes to positive attitudes and may evoke greater engagement and higher job performance. Thus, meaningful work can be regarded as a mediator of work engagement and job performance [27]. Employees who find greater meaning in their work can leverage their full potential, assist others to complete tasks and meet goals, and perform well at work [28], [29]. Several studies have shown that employees who experience a certain form of intrinsic motivation are likely to interpret it as a sign of meaningful work that is consistent with their tasks and self-concept, enhancing their job performance [30]- [32]. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Work meaningfulness positively and significantly influences job performance.

Work engagement plays a crucial role in a company’s success because employees with low work engagement cannot improve their service attitude or provide quality services to customers. Work engagement can be improved through meaningful work. A high level of work engagement is characterized by the changes made by an employee so their job becomes more enjoyable [33]. An engaged employee is more likely to adopt more effective strategies to resolve a short-term conflict such as increased job stress from a hectic work schedule [34]. Employee-perceived work meaningfulness is a key determinant of a company’s success because those who perceive their job as not meaningful cannot improve their service attitude or provide quality service to customers. Moreover, meaningful work contributes to personal security and dignity [35], and subtly increases employees’ perceptions of their work’s value and engagement. Meaningful work aligns better with employees’ life goals so they become more committed and engaged [36], [37]. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Work meaningfulness positively and significantly influences work engagement.

Work engagement is enhancing one’s job competency and performance and getting promoted to a higher position [12]. May, Gilson, and Harter [38] posited that work engagement is employees’ psychological identification with their work and their behavioral, cognitive, and affective dedication toward it. In psychology and management, work engagement is a key determinant of productivity, well-being, stress, absenteeism, attendance, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, job performance, and creativity [39]. It is also a forerunner of job performance, as employees with a positive state of mind can deal with stress confidently and optimistically, take on responsibilities, and pursue success and excellence at work [40]. Thus, work engagement affects job performance, customer loyalty, employee retention, and job satisfaction [41]. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Work engagement positively and significantly influences job performance.

Transformative leaders can convince subordinates to believe in their own capacity to meet existing objectives. As a result, subordinates are willing to work harder and perform better [42]. Transformative leaders can use public occasions and regular meetings to communicate a team’s vision, emphasize the importance of achieving group objectives, and link each employee’s objectives to the team’s vision [43]. Thus, employees are motivated to instill enthusiasm and vitality in their work and eagerly enhance their efforts to perform better. Moreover, transformative leaders strengthen team identity and cohesion [44]. Under their leadership, subordinates can exceed expectations at work because they are more engaged, perform better, and are willing to help one another [45]. The support, enlightenment, and guidance from their supervisors allow employees to perceive their jobs as more challenging, engaging, and satisfying. Hence, transformative leadership increases employees’ engagement and strengthens their self-efficacy and optimism [46], [47]. Employees may feel more optimistic after receiving quality guidance, feedback, and support, become confident in achieving their goals, and increase their work engagement and efforts [18]. Therefore, transformative leadership is one of the most effective leadership styles for enhancing organizational job performance and employees’ work engagement [48], [49]. Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4: Transformative leadership positively and significantly influences work engagement.

When work is meaningful, an employee identifies a purpose greater than the work’s extrinsic outcome, and their main goal is to be driven to find significance, personal accomplishment, and motivation [50]. Once these needs have been satisfied, the individual will pursue a more meaningful job to achieve their life goals. Therefore, experiencing meaningful work maximizes employees’ motivation and determination. Work meaningfulness not only entails performance-based rewards for employees but also shapes the connection between goals and values [50], [51]. This increases the likelihood of consistency between managers’ organizational mission and subordinates’ core values. The latter may find their job more meaningful because of its purpose, incentives, and importance. By providing sincere encouragement, transformative leaders are regarded as trustworthy people who show optimism for future goals, and, in turn, enhance subordinates’ core values [15], [52]- [54]. Transformative leaders are potential managers; they can mobilize followers who want to strive for collective goals and ambitions and those who are intrinsically devoted to their job and are willing to work hard [55], [56]. We propose the following hypothesis:

H5: Transformative leadership positively and significantly influences work meaningfulness.

Meanwhile, they expect that the reward systems will motivate employees to surpass their current job performance [11]. The main purpose of a reward system is to provide employees with material rewards (e.g., performance bonuses, promotions, and interim and final dividends for their excellent job performance). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6: Material rewards positively and significantly influence job performance.

Proactive personality traits are the employees’ reliable, persistent, organization-, and goal-oriented behaviors toward their jobs [57]. Employees with proactive personality traits often perform better at work than those without a sense of responsibility [58]. These employees are highly self-regulated and shaped by motivational skills, involving motivation control and emotion control [19]. Therefore, they can take on more complex tasks, enhancing their job performance. Employees with proactive personality traits flourish and exhibit creative behaviors that enhance their job performance [21], [22]. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7: Proactive personality traits positively and significantly influence job performance.

Fostering a proactive personality is an effective management style that encourages in-role and extra-role behaviors in employees [59]. Employees with a proactive personality motivate their peers to look beyond their self-interests, establish a high level of work efficiency and standards, develop a positive view toward work meaningfulness, assist their peers in becoming more creative and innovative, and actively express concern toward the needs of others [60], [61]. Furthermore, proactive employees seek personal growth and take on the role of counselors to motivate their peers to prioritize organizational interests over personal ones. Furthermore, leaders motivate and empower subordinates’ pride and organizational attachment, enhancing work meaningfulness. A proactive personality’s significant and positive influence on work meaningfulness has been empirically demonstrated [20], [62]. Employees with a proactive personality are highly driven and courageous. They help others deal with negative workplace stressors, overcome adversity, and enhance their identification with their job’s significance. Also, they are not easily affected by their emotions [63]. Thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

H8: Proactive personality traits positively and significantly influence work meaningfulness.

Figure 1 shows the conceptual study framework. We used covariance-based structural equation modeling for the analysis. Based on the literature review and consolidation of the research hypotheses, job performance was interpreted using five variables: transformative leadership, material rewards, work engagement, work meaningfulness, and proactive personality traits.

The questionnaire comprised two sections. The first section collected the respondents’ basic information, such as sex, marital status, age, highest education level, tenure, and type of real estate agent license held. The second section consisted of items pertaining to the latent variables of transformative leadership, material rewards, work engagement, proactive personality traits, work meaningfulness, and job performance.

Podsakoff et al. [64] identified six measures of transformative leadership: articulating a vision, providing an appropriate model for subordinates, fostering the acceptance of group goals, having high-performance expectations, providing individualized support, and promoting innovation. Bass [60] and Bass and Avolio [65] defined transformative leadership as a four-dimensional concept of individualized consideration, inspirational motivation, idealized influence, and intellectual stimulation. In our questionnaire, we designed eight items covering these four sub-dimensions. Based on the operational definitions provided by Li and Hung [66], we developed five items for the material-rewards variable across the three sub-dimensions of monetary incentive schemes (bonuses, profit sharing, performance-based rewards, outcomes sharing, and professional rewards), travel incentives, and reward schemes. Based on the study by Maslach, Schaufeli and Leiter [67], we developed four items for the work engagement variable across the three sub-dimensions of energy, involvement, and efficacy. Engaged employees are less likely to feel fatigued or slack off at work, and can fully devote themselves to completing their tasks efficiently. Costa and McCrae [57] proposed a five-factor model of personality that consisted of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, and agreeableness. We developed six items for proactive personality traits based on the operational definitions of the three sub-dimensions. Harpaz and Fu [68] suggested that job performance can be analyzed through meaning-of-work dimensions such as work centrality, entitlement norms, economic orientation, interpersonal relations, and obligation norms. We developed 10 items for work meaningfulness, based on the operational definitions of the five sub-dimensions. Borman and Motowidlo [69] stated that job performance consists of task and contextual performance. Task performance describes an employee’s work outcomes and the degree to which they complete organizational tasks and meet their work demands. On the other hand, contextual performance describes an employee’s voluntary participation in activities that are not part of their formal duties, their enthusiastic perseverance to complete tasks, and their willingness to cooperate with and help others, prioritizing organizational policies and procedures over themselves, and supporting and defending organizational goals. We developed four items for job performance, based on the operational definitions of the task performance and contextual performance sub-dimensions. All questionnaire items were measured on a five-point Likert scale: strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree. The questionnaire items are listed in Table 1.

| Dimension | Item | References | |

| 1. Transformative leadership | |||

| Individualized consideration | 1. | My supervisor provides timely assistance to help me overcome barriers in real estate sales. |

Bass and Avolio

|

| 2. | My supervisor provides timely and professional assistance to complement the incomplete and limited data collected from settings with deficient information | ||

| Inspirational motivation | 3. | My supervisor offers appropriate consolation and encouragement when competitors get a business deal before us. | |

| 4. | My supervisor provides timely assistance and guidance when I feel distressed by peer competition. | ||

| Idealized influence | 5. | My supervisor sets goals during team meetings. | |

| 6. | My supervisor sets goals for their subordinates to familiarize themselves with and achieve. | ||

| Intellectual stimulation | 7. | My supervisor provides professional sales knowledge from time to time to improve the unit’s business skills. | |

| 8. | My supervisor discloses their personal experiences to help me overcome barriers in real estate sales. | ||

| 2. Material rewards | |||

| Monetary incentives scheme | 1. | The company provides small rewards to those who achieve performance goals. |

Li and Hung

|

| 2. | The company provides big rewards to those who achieve exceptional performance. | ||

| Travel incentives | 3. | The company provides overseas travel incentives to those who meet annual performance goals. | |

| 4. | The company regularly provides employee travel incentives to boost our morale. | ||

| Rewards scheme | 5. | The company provides appropriate rewards (such as cars and mobile phones) to those with outstanding performance. | |

| 6. | The company provides appropriate rewards (such as trophies and certificates) to those who achieve performance goals. | ||

| 3. Work engagement | |||

| Energy | 1. | I believe that being driven allows me to complete sales goals. | Maslach et al. |

| 2. | I believe that being confident allows me to overcome barriers in real estate sales. | ||

| Involvement and efficacy | 3. | I believe that I have sufficient attention and confidence to devote myself to a (sales and development) business deal. | |

| 4. | I believe that I can complete the (sales and development) business deals assigned by my supervisor. | ||

| 4. Proactive personality traits | |||

| Openness | 1. | I believe that I have sufficient patience to listen to and accept others’ suggestions. | Costa and McCrea |

| 2. | I find joy in acquiring new professional knowledge. | ||

| Conscientiousness | 3. | I believe that I can devote myself to real estate sales at all times and provide immediate assistance to resolve buyer-seller problems. | |

| 4. | I believe that I can proactively provide assistance and information on (sales and development) business deals to clients. | ||

| Extraversion and agreeableness | 5. | I believe that I can proactively and cordially connect with a potential client and close business deals that benefit the company. | |

| 6. | I believe that I can proactively and positively engage in (sales and development) business deals and help the company achieve a higher sales performance. | ||

| 5. Work meaningfulness | |||

| Work centrality | 1. | I have opportunities for in-service training at work. | Harpaz and Fu |

| 2. | Working in real estate is meaningful to me. | ||

| Entitlement norms | 3. | Working in real estate aligns with my capabilities. | |

| 4. | Working in real estate is interesting to me. | ||

| Economic orientation | 5. | Working in real estate is important to me. | |

| 6. | I esteem working in real estate. | ||

| Interpersonal relations | 7. | I find it interesting to meet different people by working in real estate. | |

| 8. | Working in real estate improves my interpersonal relations. | ||

| Obligation norms | 9. | I believe that working in real estate contributes to society. | |

| 10. | I believe that working in real estate benefits society. | ||

| 6. Job performance | |||

| Task performance | 1. | I can meet the work goals set by my company. | Borman and Motowidlo |

| 2. | I can attain the job performance expected by my supervisor. | ||

| Contextual performance | 3. | In line with company plans, I can undertake philanthropic activities during my spare time to enhance the company’s image. | |

| 4. | I can support my colleagues anytime during my spare time to meet the group’s performance goals. | ||

Convenience sampling was used in this study to recruit the questionnaire respondents, who were real estate agents working in Kaohsiung City. The questionnaire was administered online as a Google form (360 copies) or on paper (500 copies). A total of 860 questionnaires were administered from December 1, 2021, to January 31, 2022. The link to the online questionnaire was forwarded to the respondents by their family and friends on social media, as the COVID-19 pandemic at the time made it unsuitable to deliver the hard copies. Twenty paper questionnaires each were delivered in person to 25 real estate companies in Lingya, Qianzhen, Xinxing, and Qianjin districts. Of the 360 online questionnaires recovered, 274 were valid and 86 were invalid (determined as all responses were either “disagree” or “agree”). Of the 500 paper questionnaires recovered, 274 were valid and 226 were invalid. In total, there were 548 valid and 312 invalid questionnaires, indicating an effective response rate of 63.7%.

| Variable | Item | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 285 | 52 |

| Female | 263 | 48 | |

| Age | 25 years and below | 15 | 2 |

| 26–30 years | 21 | 3.8 | |

| 31–35 years | 30 | 5.4 | |

| 36–40 years | 68 | 12.4 | |

| 41–45 years | 125 | 22.8 | |

| 46–50 years | 77 | 14 | |

| 51–55 years | 132 | 23.7 | |

| 56–60 years | 52 | 9.6 | |

| 61 years and above | 28 | 5.1 | |

| Highest education level | Senior/vocational high school | 5 | 1.5 |

| Junior college | 48 | 14.3 | |

| University (2-year and 4-year technical programs) | 204 | 60.9 | |

| Postgraduate | 78 | 23.3 | |

| Marital status | Married | 351 | 64 |

| Single | 197 | 35.9 | |

| Job position | Store manager | 34 | 6.3 |

| Real estate agent | 182 | 33.2 | |

| Others (administrative/sales assistant) | 332 | 60.5 | |

| Tenure | Less than 1 year | 34 | 6.2 |

| 2–4 years | 45 | 8.2 | |

| 5–7 years | 53 | 9.6 | |

| 8–10 years | 50 | 9.1 | |

| 11–13 years | 50 | 9.1 | |

| 14–16 years | 47 | 8.5 | |

| 17 years and above | 269 | 49 |

Table 2 presents the demographic characteristics of the respondents. Males accounted for 52% (285 respondents) and females accounted for 48% (263) of the sample. The predominant age group was 51–55 years (23.7%, 132), followed by 41–45 years (22.8%, 125). Most respondents were married (64%, 351) and single respondents accounted for 35.9% (197). Regarding job tenure, most respondents had worked for more than 17 years (49%, 269), followed by 5–7 years (9.6%, 53). Regarding job positions, most respondents chose “others” (60.5%, 332), followed by real estate agents (33.2%, 182). Regarding education level, most held a college degree (including two-year and four-year technical programs) (60.9%, 204), followed by those with a postgraduate degree (23.3%, 78).

Reliability analysis evaluates the consistency and stability of a measuring instrument with its test items. Consistency reflects whether the items in a test are coherent with one another. Stability reflects the degree of consistency in the scores obtained by the same group of respondents after completing the same test items repeatedly. The consistency and reliability of all the questionnaire dimensions in this study were expressed using Cronbach’s \(\alpha\). According to Nunnally [70], a Cronbach’s \(\alpha\) \(\mathrm{\ge}\) 0.7 indicates high reliability, a Cronbach’s \(\alpha\) \(\mathrm{<}\) 0.7 but \(\mathrm{\ge}\) 0.35 indicates moderate reliability, and a Cronbach’s \(\alpha\) \(\mathrm{<}\) 0.35 indicates no reliability, resulting in the removal of the item or the revision of the scale. In this study, the Cronbach’s \(\alpha\) values of the transformative leadership, material rewards, work engagement, proactive personality traits, work meaningfulness, and job performance dimensions were 0.894, 0.896, 0.865, 0.882, 0.917, and 0.856, respectively, indicating high reliability (i.e., they were all \(\mathrm{>}\) 0.7). Table 3 presents the results’ reliability.

| Dimension | Items measured | Cronbach’s \(\alpha\) |

|---|---|---|

| Transformative leadership | 8 | 0.894 |

| Material rewards | 6 | 0.896 |

| Work engagement | 4 | 0.865 |

| Proactive personality traits | 6 | 0.882 |

| Work meaningfulness | 10 | 0.917 |

| Job performance | 4 | 0.856 |

Convergent validity measures the degree of positive correlation between a measurement target and its dimensions. A standardized factor loading \(\mathrm{>}\) 0.5 can be used to determine the convergent validity. In this study, the standardized factor loadings were all \(\mathrm{>}\) 0.5 and statistically significant. The composite reliability (CR) is the internal consistency of a dimension. A CR \(\mathrm{>}\) 0.6 is the acceptable criterion. The CR of all the variables in this study was \(\mathrm{>}\) 0.8. A higher average variance extracted (AVE) indicates that a latent variable is more able to explain the variance of all its measurement items. An AVE \(\mathrm{>}\) 0.5 is the acceptable criterion. Here, the AVEs of transformative leadership, material rewards, work engagement, proactive personality traits, work meaningfulness, and job performance were all \(\mathrm{>}\) 0.5 and were highly acceptable [71]. As shown in Table 4, our results demonstrate that the questionnaire exhibited excellent convergent validity. Discriminant validity is the degree of the difference between dimensions; its criteria are: (1) The square root of the AVE of a dimension must be greater than its correlation coefficient with other dimensions. This means that there is considerable discriminant validity between the dimensions. The results presented in Table 5 show that this criterion was met and the discriminant validity was adequate. (2) The heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) criterion: According to Gaski and Nevin [72], the factor loadings of variance-based structural equation models are often overestimated, but if underestimated, the validity assessment process may not be rigorous. Thus, the HTMT criterion is a more rigorous measure of discriminant validity. An HTMT value \(\mathrm{<}\) 0.9 indicates discriminant validity between the dimensions. Here, the HTMT values of all dimensions were \(\mathrm{<}\) 0.9 and thus exhibited excellent discriminant validity (Table 6).

The empirical results are explained in two sections. The first section reports the assessment of the conceptual framework’s fit, and the second section reports the estimation results and analysis of the linear structural model.

This study measured the model’s fit based on three assessment criteria introduced by Bagozzi, Baumgartne and Yi [73]: the overall model’s fit, preliminary fit criteria, and the model’s internal structure fit.

Bagozzi et al. (1989) suggested that preliminary fit criteria should comprise the following: 1. The absence of negative measurement errors; 2. Measurement errors must achieve a level of significance; 3. The relevant absolute value between the estimated parameters must not be too close to 1; 4. The factor loadings must not be excessively low (\(\mathrm{<}\)0.5) or high (\(\mathrm{>}\)0.95); 5. The absence of large standard errors. As shown in Table 4, the measurement item loadings of the six latent variables were all significant, ranging from 0.622 to 0.914. The R\({}^{2}\) values of the endogenous latent variables of the three structural equation models were 0.652, 0.685, and 0.708, respectively. In summary, all preliminary fit criteria were acceptable.

| Variable | Unstandardized factor loading | Standardized factor loading | Error variance | Reliability of the measured variable | CR | AVE | R\(^2\) of the structural equation model |

| Transformative leadership | 0.913 | 0.727 | |||||

| Individualized consideration | 0.935 | 0.793 | 0.220 | 0.628 | |||

| Inspirational motivation | 1.088 | 0.810 | 0.264 | 0.656 | |||

| Idealized influence | 0.629 | 0.622 | 0.266 | 0.387 | |||

| Intellectual stimulation | 1.000 | 0.857 | 0.153 | 0.735 | |||

| Material rewards | 0.905 | 0.762 | |||||

| Monetary incentive schemes | 0.771 | 0.758 | 0.294 | 0.574 | |||

| Travel incentives | 1.065 | 0.914 | 0.150 | 0.835 | |||

| Reward schemes | 1.000 | 0.862 | 0.230 | 0.743 | |||

| Work engagement | 0.915 | 0.844 | 0.708 | ||||

| Energy | 1.000 | 0.810 | 0.137 | 0.656 | |||

| Involvement and efficacy | 1.061 | 0.846 | 0.117 | 0.716 | |||

| Proactive personality traits | 0.952 | 0.869 | |||||

| Openness | 0.752 | 0.689 | 0.142 | 0.475 | |||

| Conscientiousness | 0.914 | 0.856 | 0.069 | 0.732 | |||

| Extraversion and agreeableness | 1.000 | 0.858 | 0.081 | 0.736 | |||

| Work meaningfulness | 0.950 | 0.791 | 0.652 | ||||

| Work centrality | 0.903 | 0.778 | 0.150 | 0.606 | |||

| Entitlement norms | 1.016 | 0.823 | 0.136 | 0.682 | |||

| Economic orientation | 1.000 | 0.797 | 0.162 | 0.636 | |||

| Interpersonal relations | 0.695 | 0.703 | 0.140 | 0.494 | |||

| Obligation norms | 1.000 | 0.762 | 0.204 | 0.581 | |||

| Job performance | 0.868 | 0.768 | 0.685 | ||||

| Task performance | 1.000 | 0.751 | 0.199 | 0.564 | |||

| Contextual performance | 1.097 | 0.805 | 0.168 | 0.648 | |||

| Note(s): denotes p \(\mathrm{<}\) 0.01, denotes p \(\mathrm{<}\) 0.05. | |||||||

| Transformative leadership | Material rewards | Work engagement | Proactive personality traits | Work meaningfulness | Job performance | |

| Transformative leadership | 0.723 | |||||

| Material rewards | 0.703 | 0.757 | ||||

| Work engagement | 0.674 | 0.573 | 0.828 | |||

| Proactive personality traits | 0.600 | 0.526 | 0.699 | 0.865 | ||

| Work meaningfulness | 0.500 | 0.437 | 0.773 | 0.702 | 0.774 | |

| Job performance | 0.525 | 0.431 | 0.702 | 0.703 | 0.743 | 0.757 |

| Note(s): The diagonal elements shown in this matrix are the square roots of the constructs’ AVE. | ||||||

| Transformative leadership | Material rewards | Work engagement | Proactive personality traits | Work meaningfulness | |

| Material rewards | 0.837 | ||||

| Work engagement | 0.670 | 0.526 | |||

| Proactive personality traits | 0.607 | 0.492 | 0.863 | ||

| Work meaningfulness | 0.533 | 0.458 | 0.734 | 0.757 | |

| Job performance | 0.470 | 0.415 | 0.802 | 0.764 | 0.757 |

The fit of the model’s internal structure mainly assesses the level of significance of the estimated parameters within the model and the CRs of the latent variables. Bagozzi et al. [73] suggested three criteria for fitting a model’s internal structure:

1. The individual item reliability is \(\mathrm{>}\)0.50 and each factor loading is significant. The factor loadings in our model were all \(\mathrm{>}\)0.50 and thus significant (Table 4).

2. The CR of the latent variables is \(\mathrm{>}\)0.60. A higher CR indicates higher consistency. The CRs of the six latent variables in this study were all \(\mathrm{>}\)0.80 and exceeded the \(\mathrm{>}\)0.60 criterion.

3. The AVE is \(\mathrm{>}\)0.50 [71]. The AVE is the ability of a latent variable to explain the variance of each measurement. A higher AVE indicates that the latent variable has higher reliability and convergent validity. The AVEs of the six latent variables were all \(\mathrm{>}\)0.70 (Table 4). In summary, the fit of the model’s internal structure was exceptionally good.

The overall model fit assesses how the overall model fits with the data. Bollen [74] and Mulaik, James, Van Alstine, Bennett, Lind and Stilwell [75] proposed three types of overall model fit measures: absolute fit measures, incremental fit measures, and parsimonious fit measures.

Regarding the absolute fit measures, the chi-square statistic (\(\chi\)\({}^{2}\)) in this study was 348.322 (p = 0.001) and thus significant (Table 7). Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected and the conceptual model had a poor fit with the structural distribution of the sample data. This means that the conceptual model differs from the observed data. Because \(\chi\)\({}^{2\ }\)is sensitive to the sample size, other fit measures should be considered. The normal chi-square statistic (\(\chi\)\({}^{2}\)/df) was 2.977 (\(\mathrm{<}\)3). According to Hair, Anderson, Tatham and Black [76], a model has an acceptable fit when its goodness of fit index (GFI) and normed fit index (NFI) are \(\mathrm{>}\)0.90 and its root mean square residual (RMR) is \(\mathrm{<}\)0.05. Moreover, its fit is adequate when the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is \(\mathrm{<}\)0.05 and reasonable when \(\mathrm{<}\)0.08. Here, the GFI, comparative fit index (CFI), NFI, RMR, and RMSEA were 0.940, 0.967, 0.952, 0.021, and 0.060, respectively, indicating adequate fit.

Incremental fit measures are taken to improve the fit by comparing a preset model with an independent model. The two incremental fit measures in this study, namely adjusted GFI (AGFI) and CFI, were 0.952 and 0.967, respectively, and were both within an acceptable range (Table 7).

Moreover, the parsimonious fit measures used in this study, namely the parsimonious NFI (PNFI) and parsimonious CFI (PCFI), were 0.651 and 0.662, respectively, and both met the required criteria (Table 7). In summary, the overall fit of our conceptual framework was acceptable.

| Test statistic | Ideal fit standard | Test result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute fit measures | \(\chi ^{2}\)(p-value) | 348.322 | 0.001 |

| \(\chi ^{2} /df\) | \(\mathrm{<}\)3 | 2.977 | |

| \(GFI\) | \(\mathrm{>}\)0.9 | 0.940 | |

| \({\rm RMR}\) | The smaller, the better | 0.021 | |

| \(RMSEA\) | Preferably \(\mathrm{<}\)0.05; the smaller, the better | 0.060 | |

| Incremental fit measures | \(AGFI\) | \(\mathrm{>}\)0.9 | 0.902 |

| \(NFI\) | \(\mathrm{>}\)0.9 | 0.952 | |

| \(CFI\) | \(\mathrm{>}\)0.9 | 0.967 | |

| Parsimonious fit measures | \(PNFI\) | \(\mathrm{>}\)0.5 | 0.651 |

| \(PCFI\) | \(\mathrm{>}\)0.5 | 0.662 |

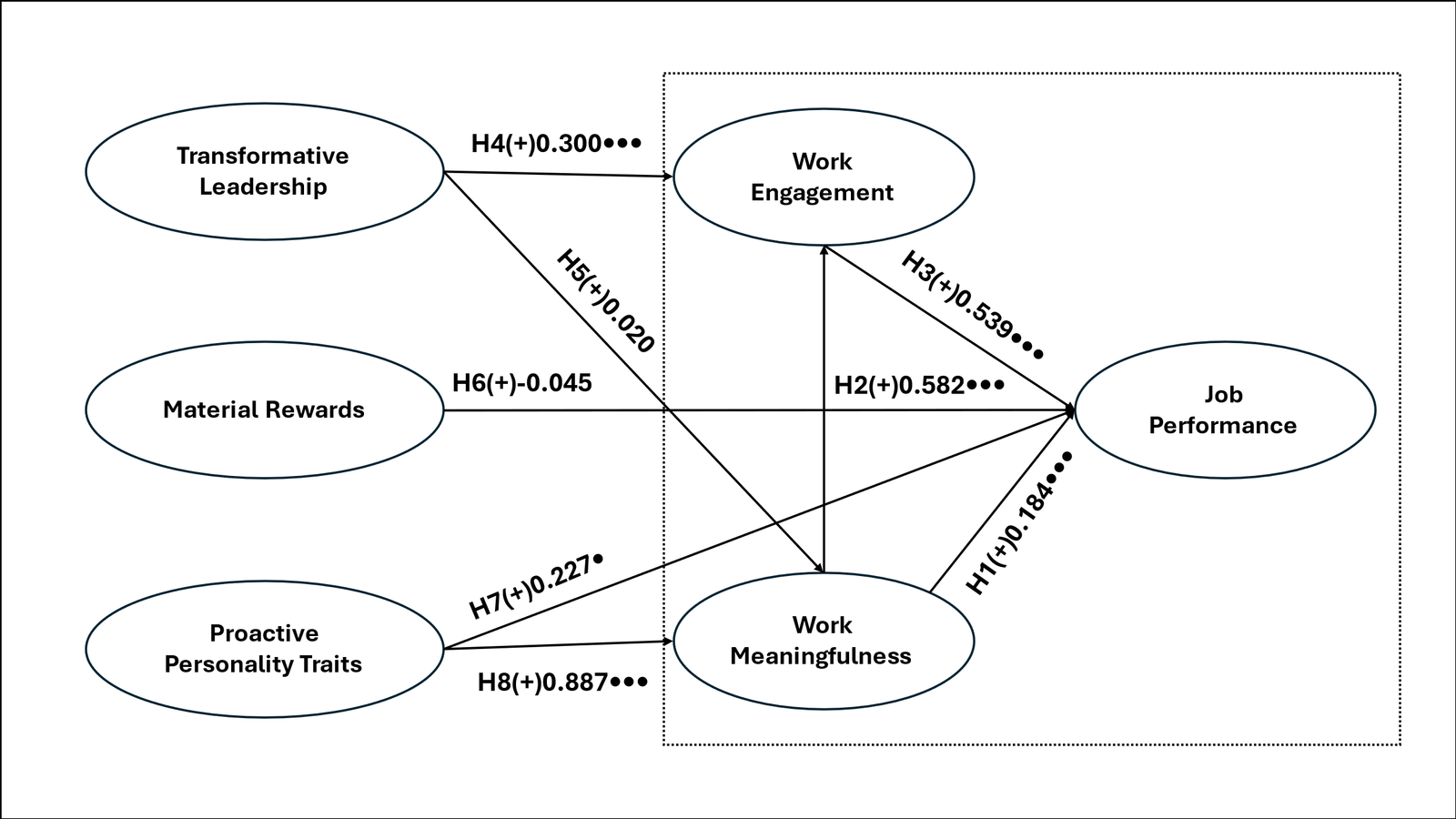

The estimation results are presented in Table 8 and Figure 2. The estimated coefficient (standardized coefficient) of the influence of work meaningfulness on job performance was 0.184 and attained a 5% level of significance. This means that work meaningfulness positively and significantly influences job performance, and H1 is supported. The estimated coefficient of the influence of work meaningfulness on work engagement was 0.582 and attained a 1% level of significance. This means that work meaningfulness positively and significantly influences work engagement, and H2 is supported. The estimated coefficient of the influence of work engagement on job performance was 0.539 and attained a 1% level of significance. This indicates that work engagement positively and significantly influences job performance, and H3 is supported. The estimated coefficient of the influence of transformative leadership on work engagement was 0.300 and attained a 1% level of significance. This indicates that transformative leadership positively and significantly influences work engagement, and H4 is supported. However, the estimated coefficient of the influence of transformative leadership on work meaningfulness was 0.020 and was not significant. This means that transformative leadership has no positive or significant influence on work meaningfulness, and H5 is not supported. The estimated coefficient of the influence of material rewards on job performance was -0.045 and was not significant. This means that material rewards have no positive or significant influence on job performance, and H6 is not supported. On the other hand, the estimated coefficient of the influence of proactive personality traits on job performance was 0.227 and attained a 10% level of significance. This means that proactive personality traits positively and significantly influence job performance, and H7 is supported. The estimated coefficient of the influence of proactive personality traits on work meaningfulness was 0.887 and attained a 1% level of significance. This indicates that proactive personality traits positively and significantly influence work meaningfulness, and H8 is supported. In summary, the empirical results supported all the hypotheses in this study, except for H5 and H6.

| Hypothesis | inter-variable relationship | Estimated coefficient | Standard error | t-ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Work meaningfulness \(\mathrm{\to}\) Job performance | 0.184 | 0.084 | 2.098 | 0.036 |

| H2 | Work meaningfulness \(\mathrm{\to}\) Work engagement | 0.582 | 0.075 | 12.129 | 0.001 |

| H3 | Work engagement \(\mathrm{\to}\) Job performance | 0.539 | 0.133 | 6.154 | 0.001 |

| H4 | Transformative leadership \(\mathrm{\to}\) Work engagement | 0.300 | 0.054 | 8.962 | 0.001 |

| H5 | Transformative leadership \(\mathrm{\to}\) Work meaningfulness | 0.020 | 0.052 | 0.530 | 0.705 |

| H6 | Material rewards \(\mathrm{\to}\) Job performance | -0.045 | 0.032 | -1.514 | 0.117 |

| H7 | Proactive personality traits \(\mathrm{\to}\) Job performance | 0.227 | 0.129 | 2.348 | 0.097 |

| H8 | Proactive personality traits \(\mathrm{\to}\) Work meaningfulness | 0.887 | 0.085 | 14.041 | 0.001 |

| Note(s): The estimated coefficient is presented as a standardized coefficient. , , and denotes a 10%, 5%, and 1% level of significance. | |||||

* , , and denote a 10%, 5%, and 1% level of significance

According to the empirical findings, the estimated coefficient of the influence of work meaningfulness on job performance was 0.184 and statistically significant. This, the empirical findings supported H1 and were consistent with the findings of Cardador et al. [30], Shamir [31], Paais and Pattiruhu [76], and Astuti, Maryati and Harsono []. Employees who identify strongly with their work’s meaning can handle its challenges proactively, thus increasing their job performance. The estimated coefficient of the influence of work meaningfulness on work engagement was 0.582 and significant. The empirical findings supported H2 and agreed with the findings of Ayers et al. [35], Luu [79], and Yadav and Dhar [80]. Thus, employees who perceive greater security and dignity through the meaning of their work are better engaged in it. The mentioned studies have reported that meaningful work increases employees’ security and dignity, concurrently enhancing work meaningfulness and work engagement. The estimated coefficient of the influence of work engagement on job performance was 0.539 and significant. Thus, the empirical findings supported H3 and aligned with the studies by Guan, Yeh, Chiang and Huan [81]. Engaged employees actively improve their prerequisite skills for other tasks, boosting their job performance. The estimated coefficient of the influence of transformative leadership on work engagement was 0.300 and significant. Thus, the empirical findings supported H4 and were consistent with those reported by Xanthopoulou et al. [18], Leyer, Hirzel and Moormann [82], and Winasis, Djumarno and Ariyanto [83]. Employees who agree with the leadership style feel happy at work and are more engaged. Thus, transformational leadership strengthens employees’ intrinsic self-efficacy and optimism.

The estimated coefficient of the influence of proactive personality traits on job performance was 0.227 and significant. Thus, the empirical findings supported H7 and aligned with the studies by Kanfer and Heggestad [19], Ayuningtias, Shabrina, Prasetio and Rahayu [84]. Emotionally stable employees have better emotional control and can deal with various challenges. Their proactive personality traits benefit their job performance. The estimated coefficient of the influence of proactive personality traits on work meaningfulness was 0.887 and significant. Thus, the empirical findings supported H8 and agreed with the work of Bergeron et al. [20], Liguori et al. [62], Yang et al. [21], and Kleine et al. [22]. Leaders with proactive personality traits encourage, teach, and assist employees in solving problems, gaining their trust. This increases the employees’ perception of their work’s meaning. Moreover, proactive leaders care for their employees’ demands and personal growth. They guide and motivate their employees to prioritize organizational interests over personal interests. Managers perceived by their employees as having proactive personality traits will actively attend to their employees’ demands, obtain better benefits for the team, inspire employees to overcome challenges and be accountable at work, and boost employees’ performance at work and the latter’s meaningfulness. On the other hand, the estimated coefficients of the influence of transformative leadership on work meaningfulness and the influence of material rewards on job performance were 0.020 and -0.045 and not significant. Thus, H5 and H6 were not supported. Our empirical results differ from the findings of Nielsen et al. [52], Piccolo and Colquitt [15], Bono and Judge [53], Spreitzer et al. [54], Malik et al. [11], Afsar and Umrani [85], Saeed, Afsar, Cheema and Javed [86], and Dessler [87]. We posit that transformative leadership did not significantly influence work meaningfulness largely because some of the employees’ needs (such as their salary, bonuses, and promotion opportunities) were not met satisfactorily. Moreover, material rewards did not significantly affect job performance, probably because of the employees’ goals and interest in their work. Most material rewards merely satisfy the physical demands of employees but not their spiritual needs. Hence, employees who identify with the leadership style while receiving suitable material rewards will most likely achieve higher job performance.

This study applied structural equation modeling to explore the factors that influence real estate agents’ job performance. The empirical results revealed that transformative leadership indirectly influenced employees’ job performance through work engagement as a mediator variable. Leaders motivate employees by conveying their values, affection, attitudes, and trust []. Transformative leaders earn their employees’ trust and respect and serve as an example. Providing employees with meaningful and challenging tasks fosters stronger teamwork and motivates them to fulfill duties through innovative approaches. Under such guidance and motivation, employees gradually improve their work engagement, enthusiasm, passion, and willingness to strive for enhanced job performance. We found that proactive personality traits indirectly influenced employees’ job performance through work meaningfulness as a mediator variable. Workers who perceive their leaders as having a proactive personality will intrinsically identify with the company’s corporate culture and management system. The meaningfulness of their work is also increased through proactive personality traits, further enhancing their job performance. Finally, work meaningfulness indirectly influenced employees’ job performance through work engagement as a mediator variable. Employees find greater meaning in their work when they experience transformative leadership or have a proactive personality, boosting their work engagement and job performance.

Employees who possess proactive personality traits are driven and can handle difficulties. Such employees regard their jobs as meaningful, purposeful, and valuable. This view increases their identification with their work. They are willing to overcome adversities and solve problems; in turn, increasing their work engagement. They do their best to achieve their and their company’s goals. Furthermore, job performance fosters better attitudes toward the job through a proactive personality. Thus, good attitudes increase work engagement. Employees perceive their jobs as meaningful and a contribution to society, and as a result, job performance increases. Transformative leaders with clear ideas and goals provide suitable guidance to their employees, enhancing the latter’s work engagement as they identify with their work and deal with adversity, boosting their job performance.

This study surveyed agents working in real estate franchises across Kaohsiung City. The job performance of employees of self-managed agencies could not be investigated because they were excluded from the sample. Hence, we recommend future studies to include real estate agents from self-managed or other types of agencies to examine their job performance. Furthermore, real estate-related industries such as marketing agencies can be included in future research because they have different organizational structures and service characteristics. Human resource training is crucial for enhancing job performance. Real estate is a human resource-oriented service industry; thus, knowledge management plays an indispensable role in personal growth and enterprise competitiveness. Hence, the knowledge structure can also be explored in a future study because it results in differences in employees’ job performance.

Irwin RD. Human resource management. Irwin McGraw Hill; 1998.

Robbins SP, Judge T. Organizational Behavior. Pearson South Africa; 2009.

Munir S, Sajid M. Examining locus of control (LOC) as a determinant of organizational commitment among university professors in Pakistan. Journal of Business Studies Quarterly. 2010 Sep 1;1(4):78.

Bailey SF, Barber LK, Justice LM. Is self-leadership just self-regulation? Exploring construct validity with HEXACO and self-regulatory traits. Current Psychology. 2018 Mar;37:149-61.

Akkermans J, Richardson J, Kraimer ML. The Covid-19 crisis as a career shock: Implications for careers and vocational behavior. Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2020 Jun 1;119:103434.

Shin SJ, Zhou J. Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Academy of Management Journal. 2003 Dec 1;46(6):703-14.

Shin SJ, Zhou J. Transformational leadership, conservation, and creativity: Evidence from Korea. Academy of Management Journal. 2003 Dec 1;46(6):703-14.

Marques-Quinteiro P, Curral LA. Goal orientation and work role performance: Predicting adaptive and proactive work role performance through self-leadership strategies. The Journal of Psychology. 2012 Nov 1;146(6):559-77.

Bass BM, Bass R. Handbook of Leadership: Theory, Research, and Application. Free Press; 2008.

Bass BM, Avolio BJ, Jung DI, Berson Y. Predicting unit performance by assessing transformational and transactional leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2003 Apr;88(2):207.

Malik MA, Butt AN, Choi JN. Rewards and employee creative performance: Moderating effects of creative self‐efficacy, reward importance, and locus of control. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2015 Jan;36(1):59-74.

Adnyani NLPR, Dewi AASK. Pengaruh pengalaman kerja, prestasi kerja dan pelatihan terhadap pengembangan karier karyawan. E-Jurnal Manajemen Universitas Udayana. 2019;8(7):4073.

Petrou P, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. Crafting the change: The role of employee job crafting behaviors for successful organizational change. Journal of Management. 2018 May;44(5):1766-92.

Pak K, Kooij DT, De Lange AH, Van Veldhoven MJ. Human Resource Management and the ability, motivation and opportunity to continue working: A review of quantitative studies. Human Resource Management Review. 2019 Sep 1;29(3):336-52.

Piccolo RF, Colquitt JA. Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal. 2006 Apr 1;49(2):327-40.

Bindl UK, Unsworth KL, Gibson CB, Stride CB. Job crafting revisited: Implications of an extended framework for active changes at work. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2019 May;104(5):605.

Tse HH, To ML, Chiu WC. When and why does transformational leadership influence employee creativity? The roles of personal control and creative personality. Human Resource Management. 2018 Jan;57(1):145-57.

Xanthopoulou D, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. International Journal of Stress Management. 2007 May;14(2):121.

Kanfer R, Heggestad ED. Motivational traits and skills: A person-centered approach to work motivation. Research In Organizational Behaviour, VOL 19, 1997. 1997 Jan 1;19:1-56.

Bergeron DM, Schroeder TD, Martinez HA. Proactive personality at work: Seeing more to do and doing more?. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2014 Mar;29:71-86.

Yang Y, Li Z, Liang L, Zhang X. Why and when paradoxical leader behavior impact employee creativity: Thriving at work and psychological safety. Current Psychology. 2021 Apr;40(4):1911-22.

Kleine AK, Rudolph CW, Zacher H. Thriving at work: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2019 Dec;40(9-10):973-99.

Carton AM. “I’m not mopping the floors, I’m putting a man on the moon”: How NASA leaders enhanced the meaningfulness of work by changing the meaning of work. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2018 Jun;63(2):323-69.

Haidt J. The moral emotions. Handbook of Affective Sciences. 2003 Sep 4;11(2003):852-70.

Rosso BD, Dekas KH, Wrzesniewski A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior. 2010 Jan 1;30:91-127.

Nord WR, Brief AP, editors. Meanings of occupational work: A Collection of Essays. Lexington Books; 1990.

Wells-Lepley M, Column WL. Meaningful Work: The Key to Employee Engagement. Business Lexicon: Weekly Wire. 2013.

Lepisto DA, Pratt MG. Meaningful work as realization and justification: Toward a dual conceptualization. Organizational Psychology Review. 2017 May;7(2):99-121.

Martela F, Pessi AB. Significant work is about self-realization and broader purpose: Defining the key dimensions of meaningful work. Frontiers in Psychology. 2018 Mar 26;9:363.

Cardador MT, Pratt MG, Dane EI. Do callings matter in medicine? The influence of callings versus careers on domain specific work outcomes. InPositive Organizational Scholarship Conference, Ann Arbor, MI 2006.

Shamir B. Meaning, self and motivation in organizations. Organization Studies. 1991 Jul;12(3):405-24.

Vermooten N, Boonzaier B, Kidd M. Job crafting, proactive personality and meaningful work: Implications for employee engagement and turnover intention. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology. 2019;45(1):1-3.

Kooij DT, van Woerkom M, Wilkenloh J, Dorenbosch L, Denissen JJ. Job crafting towards strengths and interests: The effects of a job crafting intervention on person–job fit and the role of age. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2017 Jun;102(6):971.

Knecht M, Freund AM. The use of selection, optimization, and compensation (SOC) in goal pursuit in the daily lives of middle-aged adults. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2017 May 4;14(3):350-66.

Ayers DF, Miller-Dyce C, Carlone D. Security, dignity, caring relationships, and meaningful work: Needs motivating participation in a job-training program. Community College Review. 2008 Apr;35(4):257-76.

Bailey C, Yeoman R, Madden A, Thompson M, Kerridge G. A review of the empirical literature on meaningful work: Progress and research agenda. Human Resource Development Review. 2019 Mar;18(1):83-113.

Lichtenthaler PW, Fischbach A. A meta-analysis on promotion-and prevention-focused job crafting. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology. 2019 Jan 2;28(1):30-50.

May DR, Gilson RL, Harter LM. The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology. 2004 Mar;77(1):11-37.

Parker SK, Morgeson FP, Johns G. One hundred years of work design research: Looking back and looking forward. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2017 Mar;102(3):403.

Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Taris TW. Work engagement: An emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress. 2008 Jul 1;22(3):187-200.

Rich BL, Lepine JA, Crawford ER. Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal. 2010 Jun;53(3):617-35.

Shamir B, House RJ, Arthur MB. The motivational effects of charismatic leadership: A self-concept based theory. Organization Science. 1993 Nov;4(4):577-94.

Wang XH, Howell JM. Exploring the dual-level effects of transformational leadership on followers. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2010 Nov;95(6):1134.

Sosik JJ, Jung DI. Impression management strategies and performance in information technology consulting: The role of self-other rating agreement on charismatic leadership. Management Communication Quarterly. 2003 Nov;17(2):233-68.

Breevaart K, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Derks D. Who takes the lead? A multi‐source diary study on leadership, work engagement, and job performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2016 Apr;37(3):309-25.

Bandura A. Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000 Jun;9(3):75-8.

Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1992 Apr;16(2):201-28.

Le PB, Lei H. The mediating role of trust in stimulating the relationship between transformational leadership and knowledge sharing processes. Journal of Knowledge Management. 2018 Apr 17;22(3):521-37.

Thomson III NB, Rawson JV, Slade CP, Bledsoe M. Transformation and transformational leadership:: a review of the current and relevant literature for academic radiologists. Academic radiology. 2016 May 1;23(5):592-9.

Chalofsky N. An emerging construct for meaningful work. Human Resource Development International. 2003 Mar 1;6(1):69-83.

Arnold KA, Turner N, Barling J, Kelloway EK, McKee MC. Transformational leadership and psychological well-being: the mediating role of meaningful work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2007 Jul;12(3):193.

Nielsen K, Randall R, Yarker J, Brenner SO. The effects of transformational leadership on followers’ perceived work characteristics and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study. Work & Stress. 2008 Jan 1;22(1):16-32.

Bono JE, Judge TA. Self-concordance at work: Toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Academy of Management Journal. 2003 Oct 1;46(5):554-71.

Spreitzer GM, Kizilos MA, Nason SW. A dimensional analysis of the relationship between psychological empowerment and effectiveness, satisfaction, and strain. Journal of Management. 1997 Jan 1;23(5):679-704.

M Kouzes J, Z Posner B. The Leadership Challenge: How to Make Extraordinary Things Happen in Organizations.

Gallo P, Hlupic V. Humane leadership must be the fourth industrial revolution’s real innovation. In World Economic Forum 2019 May (Vol. 15).

Costa Jr PT, McCrae RR. Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences. 1992 Jun 1;13(6):653-65.

Judge TA, Ilies R. Relationship of personality to performance motivation: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2002 Aug;87(4):797.

MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff PM, Rich GA. Transformational and transactional leadership and salesperson performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science. 2001 Mar;29:115-34.

Bass BM. Leadership: Good, better, best. Organizational Dynamics. 1985 Dec 1;13(3):26-40.

Yukl G. An evaluation of conceptual weaknesses in transformational and charismatic leadership theories. The Leadership Quarterly. 1999 Jun 1;10(2):285-305.

W. Liguori E, D. McLarty B, Muldoon J. The moderating effect of perceived job characteristics on the proactive personality-organizational citizenship behavior relationship. Leadership & Organization Development Journal. 2013 Oct 28;34(8):724-40.

Park JH, DeFrank RS. The role of proactive personality in the stressor–strain model. International Journal of Stress Management. 2018 Feb;25(1):44.

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Moorman RH, Fetter R. Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly. 1990 Jun 1;1(2):107-42.

Bass BM, Avolio BJ. Concepts of leadership. Leadership: Understanding the Dynamics of Power and Influence in Organizations. 1997 Nov 1;323:285.

Li AT, Hung YP. The relationship between mentoring functions and job performance: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Journal of Human Resource Management. 2009;9(1):23-43.

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001:52(1):397-422.

Harpaz I, Fu X. The structure of the meaning of work: A relative stability amidst change. InWork and organizations in Israel 2017 Sep 4 (pp. 87-112). Routledge.

Borman WC. Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. Personnel selection in organizations/Jossey-Bass. 1993.

Nunnally JC. An overview of psychological measurement. Clinical Diagnosis of Mental Disorders: A Handbook. 1978:97-146.

Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981 Feb;18(1):39-50.

Gaski JF, Nevin JR. The differential effects of exercised and unexercised power sources in a marketing channel. Journal of Marketing Research. 1985 May;22(2):130-42.

Bagozzi RP, Baumgartner J, Yi Y. An investigation into the role of intentions as mediators of the attitude-behavior relationship. Journal of Economic Psychology. 1989 Mar 1;10(1):35-62.

Bollen KA. Structural Equations With Latent Variables (Vol. 210), John Wiley & Sons :1989.

Mulaik SA, James LR, Van Alstine J, Bennett N, Lind S, Stilwell CD. Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin. 1989 May;105(3):430.

Hair JF Jr, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Multivariate Data Analysis. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Prentice-Hall; 1998.

Paais M, Pattiruhu JR. Effect of motivation, leadership, and organizational culture on satisfaction and employee performance. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business. 2020;7(8):577-88.

ASTUTI RJ, MARYATI T, HARSONO M. The effect of workplace spirituality on workplace deviant behavior and employee performance: The role of job satisfaction. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business. 2020;7(12):1017-26.

Luu TT. Knowledge sharing in the hospitality context: The roles of leader humility, job crafting, and promotion focus. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2021 Apr 1;94:102848.

Yadav A, Dhar RL. Linking frontline hotel employees’ job crafting to service recovery performance: The roles of harmonious passion, promotion focus, hotel work experience, and gender. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. 2021 Jun 1;47:485-95.

Guan X, Yeh SS, Chiang TY, Huan TC. Does organizational inducement foster work engagement in hospitality industry? Perspectives from a moderated mediation model. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. 2020 Jun 1;43:259-68.

Leyer M, Hirzel AK, Moormann J. IT’S mine, i decide what to change: The role of psychological ownership in employees’process innovation behaviour. International Journal of Innovation Management. 2021 Jan 11;25(01):2150013.

Winasis S, Djumarno SR, Ariyanto E. The impact of the transformational leadership climate on employee job satisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Indonesian banking industry. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt/Egyptology. 2020;17(6):7732-42.

Ayuningtias HG, Shabrina DN, Prasetio AP, Rahayu S. The effect of perceived organizational support and job satisfaction. In: 1st International Conference on Economics, Business, Entrepreneurship, and Finance (ICEBEF 2018); 2019. Atlantis Press. p. 691–6.

Afsar B, Umrani WA. Transformational leadership and innovative work behavior: The role of motivation to learn, task complexity and innovation climate. European Journal of Innovation Management. 2020 Apr 15;23(3):402-28.

Saeed BB, Afsar B, Cheema S, Javed F. Leader-member exchange and innovative work behavior: The role of creative process engagement, core self-evaluation, and domain knowledge. European Journal of Innovation Management. 2019 Jan 4;22(1):105-24.

Dessler G. Fundamentals of Human Resource Management. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River (NJ): Pearson; 2019.